As I think around Holocaust Remembrance this year, I keep coming back to my sermon from Good Friday, 2016. I am posting it here, lightly edited.

One year in two, the readings for Morning Prayer walk us through the Lamentations of Jeremiah during Holy Week. Lamentations is a small book — only a few pages — but that’s about all of it I can take. For Lamentations is, as the name suggests, a lament, in this case, a lament for the fall of Jerusalem to the armies of Babylon in 586 B.C. — words that Christians later appropriated to describe the desolation of Christ’s death. And so it was that, yesterday, those of us who were praying the chancel heard these words:

The Lord determined to lay in ruins

the wall of daughter Zion;

he stretched the line;

he did not withhold his hand from destroying;

he caused rampart and wall to lament;

they languish together…

The elders of daughter Zion

sit on the ground in silence;

they have thrown dust on their heads

and put on sackcloth;

the young girls of Jerusalem

have bowed their heads to the ground.

My eyes are spent with weeping;

my stomach churns;

my bile is poured out on the ground

because of the destruction of my people,

because infants and babes faint

in the streets of the city…

All your enemies

open their mouths against you;

they hiss, they gnash their teeth,

they cry: ‘We have devoured her!

Ah, this is the day we longed for;

at last we have seen it!’

The Lord has done what he purposed,

he has carried out his threat;

as he ordained long ago,

he has demolished without pity;

he has made the enemy rejoice over you,

and exalted the might of your foes. (Lamentations 2:8,10-11,16-17)

The words are 2500 years old, but it was impossible, this week, not to think of Brussels, Istanbul, and Ankara, all places, now, of lament. Places where people weep and mourn and stumble through rubble on the way to bury their dead. Places where the Cross is all too real.

How do we live in such a time as this? It’s not obvious; it’s particularly not obvious how to live with integrity. And if Lamentations is eerily current today, how much more so is the St. John Passion, which reveals in its pitiless gaze our tendency to scapegoat the innocent to preserve the illusion of domestic security. And so, today, I am going to ask us to do a difficult thing: to look at the Crucifixion, not only through our own eyes, through the eyes of Christian belief, but through the eyes of Pilate, who was also a true believer. Pilate, after all, was a Roman prefect: he believed in Rome, order, stability, and the form of power in which might makes right.

And he was not alone: the religious authorities of his time accepted those priorities. Over all this passion, there hangs a statement by Caiaphas, the High Priest: “it is better for you to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed.” (John 11: 50) What he means is that the Hebrew authorities should offer up Jesus to Rome in order to prevent a crackdown upon the whole people of Israel. What he means is that safety is a higher priority for him than justice.

To which the Cross of Christ replies, Whose safety?

Surely, the Cross was not a safe place for Jesus, any more than ancient Jerusalem was a safe place for anyone who did not have power —- or for anyone who did. I mentioned last year that crucifixion was common, that at one point, at the end of the Judean rebellion against Rome in A.D. 70, there were ten thousand crosses encircling the city, each with its dead body hanging from it. That does not look like safety to me, at least not for any Jew, or, for that matter, for anyone who did not accept the power of Rome. Whatever ancient Jerusalem was, it was not safe.

It is hard to read St. John’s version of the Passion without being engulfed in its atmosphere of self-reinforcing paranoia. Power rests with Pilate, but he is primarily afraid: afraid of the people he rules, afraid of the mob, afraid of the potentates back in Rome — the ones who would eventually recall him after he suppressed an uprising too harshly (perhaps because he was afraid). Over and over, Pilate attempts to wash his hands of this affair (and not only when he actually does): “Take him back,” Pilate pleads when they first bring Jesus to him. “Do you want me to release him for you?” And, later, “I find no case against him,” three times. And, in the middle of it all, the deadly sentence, the one that echoes Caiaphas’ cynicism: “What is truth?”

What is truth? Then, as now, to the agents of power, truth is largely what they say it is. Pilate can go in one minute from asserting that he finds no case against Jesus to branding him a criminal and sending him to die. For him, as for so many, there is no truth: there is only expediency. Pilate can write the words “King of the Jews” upon Jesus’ cross in three languages because he knows the words are meaningless. Words are defined with more words; they do not ever break from their own self-contained realm to touch anything concrete, anything that has life and breath and being, and so there is no reality to stop the flow of lies. The claim of authority replaces objective truth; the innocent becomes an insurgent; Christ is nailed to the cross.

The Cross, of course, was meant to be a show of power: the power of Rome to keep its citizens and its subjects safe. The writer Elaine Scarry, who is the author of a cheerless book called The Body in Pain, analyzes the dynamics of torture this way: “For the torturer, it is not enough that the prisoner experience pain. Its reality, although already incontestable to the sufferer, must be made equally incontestable to those outside the sufferer. Pain is therefore made visible in the multiple and elaborate processes that evolve in producing it.” (Scarry 52) The Cross, then, becomes the image of Roman power, which it publicly defines, not as the power to build roads or bridges or aqueducts, not as the power of Latin and engineering and education, but as the power to cause pain to those who stand in its way. All those other powers, compelling in their own right — education, aspiration, technological prowess, the citizenship of the free — rest on this one power: the power to crush flesh and blood and bone. For Pilate, as for the world he creates, the power of Rome is magnified by the very cruelty it is able to motivate in its defenders. (Scarry, 36) Torture becomes its own justification: the broken bodies of the condemned a kind of glory.

For the torturer himself, Scarry points out, “his blindness, his willed amorality, is his power.” (Scarry 57) In a world in which most of us willingly embrace the limitations imposed on us by ethics and morality, the amoral man has a terrible form of freedom. Pilate is able to condemn Jesus precisely because he does not believe in the primacy of justice. And he is able to live with himself through those repeated attempts to deny his complicity in his own actions. When Pilate says, over and over, “I find no case against him,” he means that the crowd is forcing him to act: “You are making me do this.” Nineteen hundred years later, when Heinrich Himmler explained his actions, he used the same strategy: instead of admitting that he had done terrible things, he would claim the status of a pawn or a victim, one who had been made to see terrible things out of his duty to his country.[1]

All this matter of defining and redefining the world is at stake when Jesus stands before Pilate. Pilate asks him to acknowledge that the world is ordered as Pilate sees it: “Do you not know that I have the power to release you, and power to crucify you?“ But Jesus refuses to comply, saying instead, “You would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above.” (John 19:10-11) Against the power of Pilate to crush and to compel, Jesus pits the power of God, our God, for whom safety is not a higher priority than justice, because justice is what grants us safety.

When Jesus confronts Pilate, evoking, not the brutal power of earthly rulers, but the love that moves the sun and the other stars, he breaks through the maze of empty words to touch the truth of God. In that one gesture, he opens a space for conscience: “My kingdom is not of this world,” he says, and we are citizens of that kingdom, the one whose law is not the blood-soaked law of power but God’s rule of mercy and grace and freedom. We who follow Christ have been given space to act: space to think, space to resist, space to do justice, and not just to comply with the inexorable demands of fear. There is no freedom greater than the freedom of a Christian, if we choose to claim it, for we fear not what can shatter our body, but what can harm our soul — which has already been redeemed by the unbreakable power of God.

Looking upon the Cross, we see the limitations of our earthly logic. Pilate was not wrong in his calculations of state: what would keep the peace for now, what would enforce his own power, what would keep a subject people subjected, their leaders co-opted, their rebels silent. Our human logic will always lead us to defend our own, however we define that. But on the Cross, Christ saved us from the iron law of logic, overcame it with his perfect justice and love. He died for all the world, so that all the world might be redeemed. He made an “us” without a “them.” His death and resurrection made a mockery of Roman power, by showing not their ability to crush and to destroy, but God’s power to create and to give life. God overcame, not evil, but us.

Why am I saying these things to you today?

Do you need me to explain?

We live in a world in which the public conversation increasingly seeks to find the right balance between the important demands of ensuring the public safety and ensuring freedom and justice for the innocent. No one seems able to find the right balance. In times like these, we need to remember that there is a small step between our fear and the mockery of those whom we fear; between our mockery and the torture of those whom we have mocked; between accepting the torture of those who might be guilty (or who might not) and condoning the death of the innocent. A set of very small steps.

My colleague Emily pointed out that while Jesus knew who would betray him, Judas almost certainly did not. Judas must have followed Jesus for the same reasons the others did: because something in Jesus’ life and words spoke to the depths of Judas’ heart. At that moment, that beginning, there was no way Judas could have predicted his future actions, whether they stemmed from disillusionment with Jesus or from his belief that this set of actions would be the best way to bring about the divine intervention he believed in. No more can we predict how our ideals will lead us astray into actions we bitterly regret, or into inaction that will haunt us for years. Complacency is a sin not one of us can afford.

In 1940, the theologian Reinhold Neibuhr condemned the leaders of liberal Christianity, saying that they were “unable to distinguish between the peace of capitulation to tyranny and the peace of the Kingdom of God.”[2] He condemned them for seeing love and not grace as the center of the Gospel, reminding them that there is nothing in the Gospel that says human beings can be perfected in this life, or that we can live in perfect justice or in perfect love. Rather, the gift of the Cross is grace: God’s power coming to stand in the balance, to condemn our sin and to redeem our sorry skins, not because of our vision and courage, but in spite of our blindness and fear.

Neibuhr writes, “In its profoundest insights, the Christian faith sees the whole of human history as involved in guilt, and finds no release from guilt except in the grace of God. The Christian is freed by that grace to act in history, to give his devotion to the highest values he knows, to defend those citadels of civilization of which necessity and historic destiny have made him the defender; and he is persuaded by that grace to remember the ambiguity of even his best actions. If the providence of God does not enter the affairs of men to bring good out of evil, the evil in our good may easily destroy our most ambitious efforts and frustrate our highest hopes.”[3]

The thing is: on the most basic level, Caiaphas was right. It is better that one person die than that a whole people perish. But that does not allow us to inflict that death or that suffering on people we fear just because it’s expedient. We can defend what is true and beautiful and good. We are compelled to defend it, even at the cost of our lives. But we are not allowed to do so by sacrificing the innocent, not even when it has been re-named as justice. What is speaking through Caiaphas is not logic, but fear.

The tragedy — our tragedy and that of the Cross — is that they so often look and sound the same.

[1] Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem, cited in Scarry, 58.

[2] “Why the Christian Church is Not Pacifist,” 1940.

[3] Ibid. Italics mine.

All this week, my friend Kym and I have had a texting chain going about Advent calendars — those funny calendars with twenty-four numbered doors or drawers that people use to count down to Christmas Eve. It started when Kym sent me a link with the note, “Amazon is a minion of satan.” When I clicked on the link, I found an ad for an Advent calendar entirely filled with high-end beauty products, aptly named “Ritual.” Kym added: “not sure the message of Advent is luxurious comforts.” Then I scrolled down the link and found a calendar which contained a lego Star Wars figurine for each day of Advent, which I secretly wanted, so I sent that back. Kym didn’t think that one was quite “on point” either. And so we were off, sending them back and forth, until I stumbled upon an Advent calendar filled with our favorite perfume. Finally, I sent her my hard-earned wisdom: “We could be having a great Advent if only we did not believe in Jesus.”

All this week, my friend Kym and I have had a texting chain going about Advent calendars — those funny calendars with twenty-four numbered doors or drawers that people use to count down to Christmas Eve. It started when Kym sent me a link with the note, “Amazon is a minion of satan.” When I clicked on the link, I found an ad for an Advent calendar entirely filled with high-end beauty products, aptly named “Ritual.” Kym added: “not sure the message of Advent is luxurious comforts.” Then I scrolled down the link and found a calendar which contained a lego Star Wars figurine for each day of Advent, which I secretly wanted, so I sent that back. Kym didn’t think that one was quite “on point” either. And so we were off, sending them back and forth, until I stumbled upon an Advent calendar filled with our favorite perfume. Finally, I sent her my hard-earned wisdom: “We could be having a great Advent if only we did not believe in Jesus.” point: Advent is about preparing ourselves for an encounter with the living God, who cannot be managed or domesticated, but only served, revered, and adored.

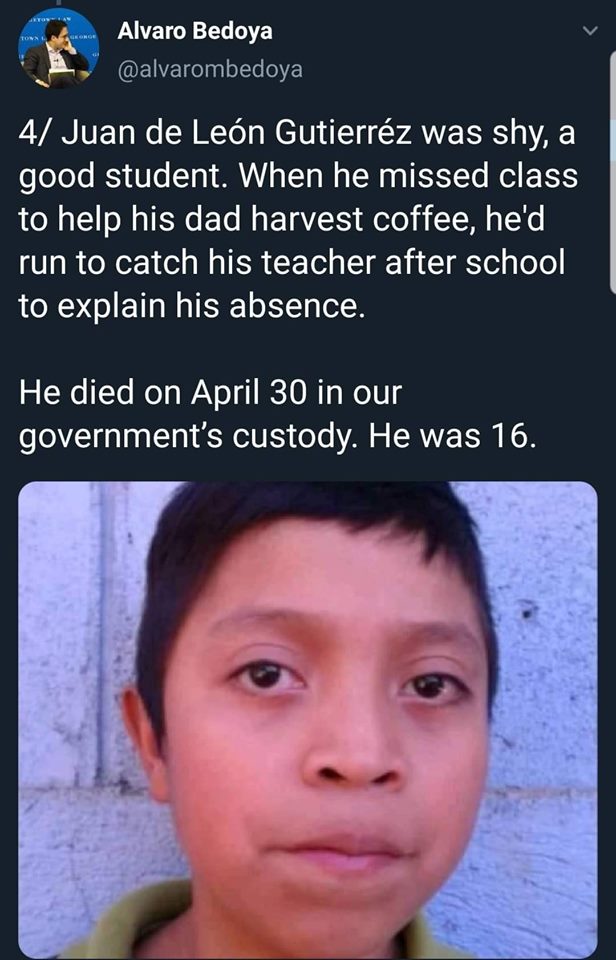

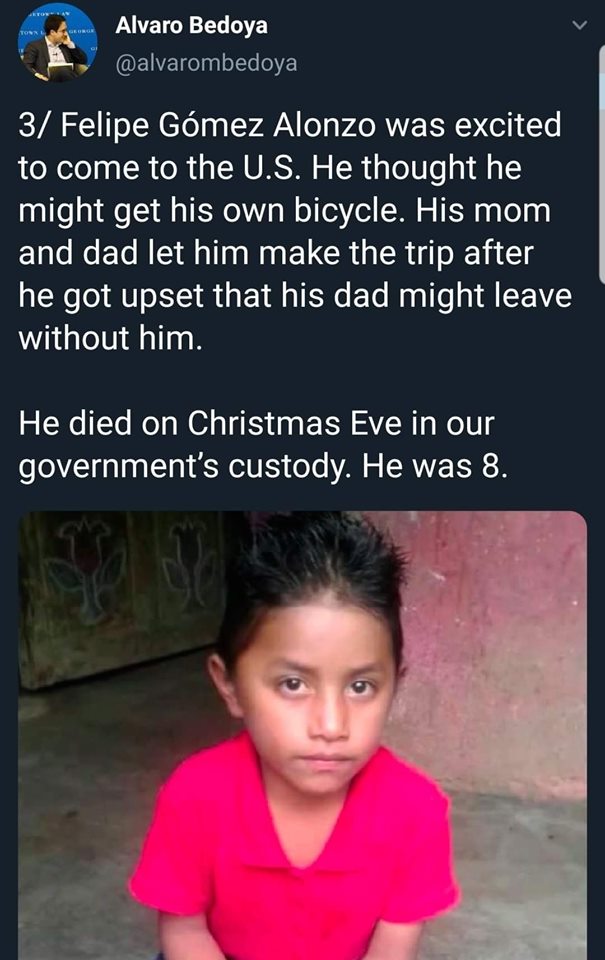

point: Advent is about preparing ourselves for an encounter with the living God, who cannot be managed or domesticated, but only served, revered, and adored. from our preoccupation with self and with family, and urges us to embrace our “responsibility to [those] whose only claim on [us] is the height and depth of their need.” And this is a deeper and more profound spiritual challenge, not only to love the Babe of Bethlehem, who is inherently adorable, but to love those who are not: all the babies in all the mangers who cry out for our compassion and mercy. And so this judgment to which we each go is really gift: in holding us accountable to what is holy and true, it frees us from all that is not love.

from our preoccupation with self and with family, and urges us to embrace our “responsibility to [those] whose only claim on [us] is the height and depth of their need.” And this is a deeper and more profound spiritual challenge, not only to love the Babe of Bethlehem, who is inherently adorable, but to love those who are not: all the babies in all the mangers who cry out for our compassion and mercy. And so this judgment to which we each go is really gift: in holding us accountable to what is holy and true, it frees us from all that is not love. At the beginning of my last year in seminary, I stepped into a class on evil. The professor, Shannon Craigo-Snell, opened the class by reading us a passage from John Calvin. I don’t have the precise reference here, but it described heaven as a place of transcendent joy and emphasized that even when our world below was shaken, still all in heaven was clear and calm and bright. Craigo-Snell put down the text and asked us, “Do you find that comforting?”

At the beginning of my last year in seminary, I stepped into a class on evil. The professor, Shannon Craigo-Snell, opened the class by reading us a passage from John Calvin. I don’t have the precise reference here, but it described heaven as a place of transcendent joy and emphasized that even when our world below was shaken, still all in heaven was clear and calm and bright. Craigo-Snell put down the text and asked us, “Do you find that comforting?”

In the last week, there has been a vigorous debate concerning a few incidents in which a member of President Trump’s leadership was refused service at a restaurant, and in which two others were heckled while trying to eat Mexican food at local establishments. The debate has focused on the idea of civility: whether and to what degree our nation is harmed when the tenor of discourse becomes rancorous.

In the last week, there has been a vigorous debate concerning a few incidents in which a member of President Trump’s leadership was refused service at a restaurant, and in which two others were heckled while trying to eat Mexican food at local establishments. The debate has focused on the idea of civility: whether and to what degree our nation is harmed when the tenor of discourse becomes rancorous. and in certain media, but I am the child of federal workers, and I can say that they and their colleagues did their best to render faithful and informed service to this nation under Presidents and Congresses of both parties. And they kept confidential what was meant to be kept confidential, and they spoke their opinions to the national leadership both when they agreed with what was being done and when they disagreed in principle or thought they had a better way to accomplish the goal. I was and am proud of them for honoring this tradition, and I continue to believe that it is the best option for our nation.

and in certain media, but I am the child of federal workers, and I can say that they and their colleagues did their best to render faithful and informed service to this nation under Presidents and Congresses of both parties. And they kept confidential what was meant to be kept confidential, and they spoke their opinions to the national leadership both when they agreed with what was being done and when they disagreed in principle or thought they had a better way to accomplish the goal. I was and am proud of them for honoring this tradition, and I continue to believe that it is the best option for our nation. heritage is knowing that my ancestors were slaughtered by nice people. (I say that without irony.) Most of the people who killed my ancestors were loving parents, good citizens, careful cooks, lovers of good music, churchgoers, people who were kind to their friends. I would probably have socialized with them without any qualms at all. In fact, the pictures attached to this post are of Nazi concentration camp workers, doing things I enjoy doing: eating blueberries, laughing in the sun with their friends, tending small children, playing with a dog. They lacked only two things: courage and integrity. And when the war was over and they were put on trial in Nuremberg and held to account for their actions, each person said more or less the same thing: We were only following orders. We did what we were told.

heritage is knowing that my ancestors were slaughtered by nice people. (I say that without irony.) Most of the people who killed my ancestors were loving parents, good citizens, careful cooks, lovers of good music, churchgoers, people who were kind to their friends. I would probably have socialized with them without any qualms at all. In fact, the pictures attached to this post are of Nazi concentration camp workers, doing things I enjoy doing: eating blueberries, laughing in the sun with their friends, tending small children, playing with a dog. They lacked only two things: courage and integrity. And when the war was over and they were put on trial in Nuremberg and held to account for their actions, each person said more or less the same thing: We were only following orders. We did what we were told.