Jesus said, “If a kingdom be divided against itself,

that kingdom cannot stand. And if a house be divided against itself,

that house cannot stand.” (Mark 3:24-25)

You’d have to be willfully blind not to notice that these are anxious times in our nation. Whoever you are, wherever you fall on the political spectrum, it’s hard to  escape the sense that we are a house bitterly divided: by political affiliation, by race, by degrees of wealth and of education, by gender, by national origin, by ideals of the good life and of who should be included in it. Each day, the rhetoric gets more heated, with Republicans and Democrats accusing one another of crimes, sending out clickbait, comparing one another to Nazis. Every day and every night, our pundits go at it, on Fox, on CNN, on Breitbart, on CNBC and NPR, tossing around names and strategies as if they were calling a boxing event: Pelosi, Schumer, Trump, Obama, Ryan, Bannon, Republican, Democrat, Centrist, Extremist, asking, Who’s gonna win? Who’s gonna win? Who’s gonna win?

escape the sense that we are a house bitterly divided: by political affiliation, by race, by degrees of wealth and of education, by gender, by national origin, by ideals of the good life and of who should be included in it. Each day, the rhetoric gets more heated, with Republicans and Democrats accusing one another of crimes, sending out clickbait, comparing one another to Nazis. Every day and every night, our pundits go at it, on Fox, on CNN, on Breitbart, on CNBC and NPR, tossing around names and strategies as if they were calling a boxing event: Pelosi, Schumer, Trump, Obama, Ryan, Bannon, Republican, Democrat, Centrist, Extremist, asking, Who’s gonna win? Who’s gonna win? Who’s gonna win?

With due respect to everyone in the room, I’d like to suggest that if that’s the question we are asking, we are all going to lose. As the pledge of allegiance reminds us, we are called to be one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all, and we stand or fall together. We have never lived fully into that aspiration — for the first seventy years of our nation’s history, women, African-Americans, and poor white men were not allowed to vote — but we have been guided by that sense of liberty and justice in such a way that we have, gradually and at a high cost, pushed against our own limitations in an attempt to extend liberty and justice to all. That’s why it is so frightening now to hear ourselves demonize one another, speak of fellow citizens as if they were enemies of all that is good and honorable and true. It is contrary to the better angels of our nature, and it is damaging to our republic. A house divided cannot stand.

The causes of our division are manifold, rooted in history and economics and regional ideology and the different ways in which we think of identity, but I think that underneath it all is a deep-rooted spiritual malaise, one which is illuminated by our reading from Samuel — our fundamental ambivalence about our freedom.

The scene opens when Samuel is in his old age. Samuel had been called by God as a child and had led the people of Israel faithfully and well, but now they come to him and demand a king, saying, “We will have a king over us, that we may be like the other nations.” (I Sam 8:20) It seems like a reasonable enough request, to be governed like other nations. What could go wrong??

The answer lies in what came before the kingship, when Israel was not like other nations precisely because the other nations were led by men, but Israel was led directly by God. When the Hebrews came out of Egypt, God dwelt among them in the form of a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. God signaled when they should march and when they should remain in camp. And while Moses governed the people day to day, when there was a particularly vexing issue, he could enter into the direct presence of God and ask for wisdom. Following Moses’ death, Joshua appeared, then a series of men and women who are known as judges. Judges arose on an ad hoc basis, mostly when Israel was facing some kind of threat. Each was called directly by God; each led Israel for a time; but none passed on the leadership to their offspring. They were more like presidents than kings: chosen for a season, with the understanding that they would not be in leadership forever.

In a system with temporary leaders, true authority remains vested elsewhere: with the people, and, in the case of the Hebrews, with God. That’s why, when the Hebrews demand a king, God comforts Samuel, saying, “They have not rejected you. They have rejected me.” (I Sam 8:7) The one thing that the system of judges required was faith: faith that God would raise up leaders when they were needed, and faith that the people would come to one another’s defense when those leaders called. It was a system that endowed the Hebrew people with powerful freedom — freedom to make choices, freedom to respond to the Spirit of God.

Samuel brought that lesson home when he tried to warn them of the dangers of monarchy. He shows them what it will look like when the resources that are meant to sustain everyone — food, drink, livestock, human labor — are diverted instead to serve the whims of one man and his family and their overweening need for power and for display. He gives them a choice between an egalitarian society and one in which the many serve the needs of the few — and the Hebrews choose the latter. They opt to  surrender their freedom for what they believe to be security. When they ask for a king, they ask for a strong man, a leader who will “fight their battles for them”— as if any king could fight a battle without an army! The truth was that the Hebrews were going to be fighting their own battles, either under the leadership of God or of a mortal man. And yet, they feared the demands imposed by freedom. They renounced responsibility for their own lives, and displaced it onto a leader.

surrender their freedom for what they believe to be security. When they ask for a king, they ask for a strong man, a leader who will “fight their battles for them”— as if any king could fight a battle without an army! The truth was that the Hebrews were going to be fighting their own battles, either under the leadership of God or of a mortal man. And yet, they feared the demands imposed by freedom. They renounced responsibility for their own lives, and displaced it onto a leader.

Looking at America in the 21st century, it is hard not to suspect that we may have engaged in a similar displacement. A strong sense of personal and civic responsibility lay at the roots of our national project. In the 1830s, when Alexis de Toqueville visited the United States, he was astonished at the culture of civic volunteerism. He wrote, “Americans use associations to give fêtes, to found seminaries, to build inns, to raise churches, to distribute books, to send missionaries to the antipodes; in this manner they create hospitals, prisons, schools. Finally, if it is a question of bringing to light a truth or developing a sentiment with the support of a great example, they associate…As soon as several inhabitants have taken an opinion or an idea they wish to promote in society, they seek each other out and unite together once they have made contact. From that moment, they are no longer isolated but have become a power seen from afar whose activities serve as an example and whose words are heeded.” He described, in other words, a vibrant civic culture, one in which Americans worked together for the common good, even though most of them did not yet have the right to cast a ballot.

If you look at the United States today, that spirit of engagement has drained away, replaced by the more-or-less complete privatization of our lives. The unrelenting pressures of the job market have eroded the time we have available to give to one another. When we do get home, the temptation is to grab whatever time we have to be with our families, or just turn on the television and zone out, or ingest a substance and zone out, or go shopping and drown our anxieties in a flood of unnecessary consumer activity. If we do notice what is going on around us, we flood the internet and social media with commentary — none of which actually engages the tools we have been given, as citizens of a democracy, to effect real change. And if all that seems isolated and hollow, mental health professionals will give you pills to dull your pain, rather than engaging in costly talk therapy that might motivate us to change our lives. In contrast to the promise of our democracy, many of us feel sharply disempowered, too small to make a difference even for the things we care about, and too focused on our own survival to care that our neighbor is drowning. And then we become frustrated and bitter that our government is not managing to do what we, ourselves, were meant to be doing for one another.

The Bible reminds us, however, that human nature is not weak, but strong, infused with the image and vitality of God. Adam and Eve did not understand this: when the serpent whispered to Eve, “You shall be like a god,” she forgot in whose image she had been made. To lure her to transgress, the serpent offered what she already had in full measure, and in agreeing to be seduced, Adam and Eve became in fact the debased and weak creatures they thought they had been all along.

But in Christ, God has restored our agency. He has healed our human nature and returned to us our power and our strength and our courage and our hope. When God raised Jesus from the dead and left the disciples and Mary Magdalene to peer into an empty tomb, he showed us that all our anxieties are paper tigers. The bad things of this world may leave scars in our flesh, but they cannot contain the life of God that surges within us and lifts us from the ashes and frees us to claim our freedom.

Witness St. Paul: born in Judaism, he persecuted the early disciples of Jesus, encountered God and underwent a radical conversion, and spend the rest of his life traveling all over the Roman Empire — on foot, by boat, in danger, in peace — proclaiming the good news of Jesus Christ, until he was captured and brought to his martyrdom.

Paul was propelled by a strong faith: faith in God, yes, but, more specifically, faith that God would use him, Paul, to make a difference in this world. For Paul, conviction and action were inseparable: “I believed, therefore have I spoken.” (II Cor 4: 13) He knows that belief is a verb, not simply a disposition of the heart, a verb which propels us outward in the service of others. “All things are for your sakes,” he writes, and then he explains the source of his strength: “though our outward man perish, yet the inward man is renewed day by day. For this slight momentary affliction is preparing us for a weight of glory eternal in the heavens.” (II Cor 4:16-17) Paul has his security, a security that is found not in the size of an army or the strength of a warrior, but in the unbreakable promise of God: that even if Paul’s body, his earthly tent, is dissolved, “we have a home prepared for us, eternal in the heavens.” (II Cor 5:1) He knows that no power on earth can destroy him, that no loss on earth will be final, that even death will not have the final word. And knowing these things, he takes courage — courage to speak what is true and to do what is right.

Paul shows us the true nature of Christian faith: it propels us out of our private sanctuaries (which too easily fetter us in isolation) and turns us back to the world. Always, we are tempted to surrender our power: to God, to man, to the state, to a leader. But what if we are not meant to surrender it, but to use it? It is, after all, the power to do good, to use our creativity in the service of the welfare of everyone in our society. And that is not a matter of forcing everyone to become Christian, but of being a Christian to everyone — of honoring them with Christ’s own love. There is only one place in which

Jesus speaks of the criteria by which we will ultimately be judged, and his criterion is si

mple: “as you have done it to the least of these my brothers, you have done it to me.”(Matt 25:40)

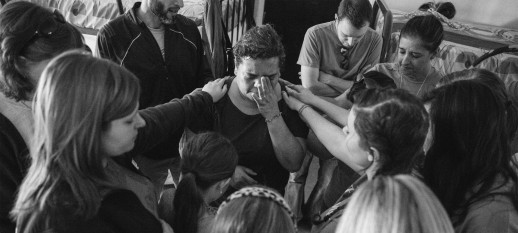

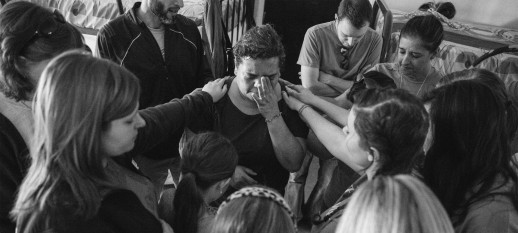

The healing of our divided house does not rest in the hands of any leader, but in ours. We are the ones who know the needs of our communities; we are the ones who have the capacity to respond — to give, to care, to act. There is no king or strongman or president who can save us from that responsibility, and no savior will do so. After all, it is our very God and savior who has given us that freedom, who has commanded us to love our neighbor and our enemy and the stranger at our gates, to name them our brothers  and sisters and mothers. This world is in our hands, and that is a daunting challenge. But we are in God’s hands, and with God, all things are possible.

and sisters and mothers. This world is in our hands, and that is a daunting challenge. But we are in God’s hands, and with God, all things are possible.

** De Tocqueville quotes are from Democracy in America, 1835, 1840. The analysis of our contemporary culture is indebted to Bruce E. Levine, “Are Americans a Broken People?”, rawstory.com, June 5, 2018.

escape the sense that we are a house bitterly divided: by political affiliation, by race, by degrees of wealth and of education, by gender, by national origin, by ideals of the good life and of who should be included in it. Each day, the rhetoric gets more heated, with Republicans and Democrats accusing one another of crimes, sending out clickbait, comparing one another to Nazis. Every day and every night, our pundits go at it, on Fox, on CNN, on Breitbart, on CNBC and NPR, tossing around names and strategies as if they were calling a boxing event: Pelosi, Schumer, Trump, Obama, Ryan, Bannon, Republican, Democrat, Centrist, Extremist, asking, Who’s gonna win? Who’s gonna win? Who’s gonna win?

escape the sense that we are a house bitterly divided: by political affiliation, by race, by degrees of wealth and of education, by gender, by national origin, by ideals of the good life and of who should be included in it. Each day, the rhetoric gets more heated, with Republicans and Democrats accusing one another of crimes, sending out clickbait, comparing one another to Nazis. Every day and every night, our pundits go at it, on Fox, on CNN, on Breitbart, on CNBC and NPR, tossing around names and strategies as if they were calling a boxing event: Pelosi, Schumer, Trump, Obama, Ryan, Bannon, Republican, Democrat, Centrist, Extremist, asking, Who’s gonna win? Who’s gonna win? Who’s gonna win? surrender their freedom for what they believe to be security. When they ask for a king, they ask for a strong man, a leader who will “fight their battles for them”— as if any king could fight a battle without an army! The truth was that the Hebrews were going to be fighting their own battles, either under the leadership of God or of a mortal man. And yet, they feared the demands imposed by freedom. They renounced responsibility for their own lives, and displaced it onto a leader.

surrender their freedom for what they believe to be security. When they ask for a king, they ask for a strong man, a leader who will “fight their battles for them”— as if any king could fight a battle without an army! The truth was that the Hebrews were going to be fighting their own battles, either under the leadership of God or of a mortal man. And yet, they feared the demands imposed by freedom. They renounced responsibility for their own lives, and displaced it onto a leader. and sisters and mothers. This world is in our hands, and that is a daunting challenge. But we are in God’s hands, and with God, all things are possible.

and sisters and mothers. This world is in our hands, and that is a daunting challenge. But we are in God’s hands, and with God, all things are possible. That is the central question which confronted the disciples in the dark days following the crucifixion of Christ, and it is their answer we honor today as we commemorate the Feast of St. Matthias. The election of Matthias as a kind of substitute apostle to take the place forfeited by Judas is remarkable, not for its occurrence, but for its context. The world of the of disciples had been shattered. For three years, they had lived in community and in hope, they had learned and grown and prayed; all that had been ripped away in the brutal slaughter of the man they had hoped would save them. They had come to the time of need; they had failed to protect the one they loved; they had learned that were not the men they had hoped to be.

That is the central question which confronted the disciples in the dark days following the crucifixion of Christ, and it is their answer we honor today as we commemorate the Feast of St. Matthias. The election of Matthias as a kind of substitute apostle to take the place forfeited by Judas is remarkable, not for its occurrence, but for its context. The world of the of disciples had been shattered. For three years, they had lived in community and in hope, they had learned and grown and prayed; all that had been ripped away in the brutal slaughter of the man they had hoped would save them. They had come to the time of need; they had failed to protect the one they loved; they had learned that were not the men they had hoped to be. In her haunting story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” Ursula LeGuin describes a city that is a kind of utopia. Omelas is beautiful; set by the seashore and lush with trees, graced with harmonious architecture that delights the eye while it fosters community among its inhabitants. Life there is good: food is plentiful; the streets are peaceful; the pace of life is moderate; and days of work are punctuated with festivals which gather all in the city, young and old, for dancing and music and athletic competition and mutual joy.

In her haunting story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” Ursula LeGuin describes a city that is a kind of utopia. Omelas is beautiful; set by the seashore and lush with trees, graced with harmonious architecture that delights the eye while it fosters community among its inhabitants. Life there is good: food is plentiful; the streets are peaceful; the pace of life is moderate; and days of work are punctuated with festivals which gather all in the city, young and old, for dancing and music and athletic competition and mutual joy. then people with courage and intelligence and grit and gumption pick themselves up and head toward other societies, places which hold out hope of a better life, or seem to.

then people with courage and intelligence and grit and gumption pick themselves up and head toward other societies, places which hold out hope of a better life, or seem to.

Today is an eerie day. Yesterday was a day of horror: marchers with torches, KKK members with robes and flags and foolish-looking shields; clergy in robes facing miliamen in body armor, carrying huge guns; the sudden hurtling of a gray car into human flesh and bone.

Today is an eerie day. Yesterday was a day of horror: marchers with torches, KKK members with robes and flags and foolish-looking shields; clergy in robes facing miliamen in body armor, carrying huge guns; the sudden hurtling of a gray car into human flesh and bone.

“Is that sugar?” The little boy’s eyes were bright with curiosity. “Why is there sugar in a museum?” The adults with him, who appeared to be his mother and grandmother, remained silent, but the boy asked again, “Why is there sugar here?” The two women looked at each other darkly. I felt for them. The four of us were standing on the first level of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, and that sugar was part of the exhibit on slavery. How do you tell a small child that a whole world lost its moral compass so badly that for hundreds of years, they would have been willing to buy and sell and beat and kill him in order to get that sugar, so that their cakes might be light and fluffy, and their coffee not too bitter (at least, to those who were privileged to drink it)?

“Is that sugar?” The little boy’s eyes were bright with curiosity. “Why is there sugar in a museum?” The adults with him, who appeared to be his mother and grandmother, remained silent, but the boy asked again, “Why is there sugar here?” The two women looked at each other darkly. I felt for them. The four of us were standing on the first level of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, and that sugar was part of the exhibit on slavery. How do you tell a small child that a whole world lost its moral compass so badly that for hundreds of years, they would have been willing to buy and sell and beat and kill him in order to get that sugar, so that their cakes might be light and fluffy, and their coffee not too bitter (at least, to those who were privileged to drink it)?

Growing up in Alexandria, Virginia, as I did, the Revolutionary War becomes an intimate friend. After all, we were minutes from the homes of George Washington, George Mason, and Lighthorse Harry Lee, and an easy day-trip from Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. The old part of our town had been an important Revolutionary-era port, and it was not unusual to see bellringers in colonial garb walking down the sidewalks, or parades of minutemen with canon and fife.

Growing up in Alexandria, Virginia, as I did, the Revolutionary War becomes an intimate friend. After all, we were minutes from the homes of George Washington, George Mason, and Lighthorse Harry Lee, and an easy day-trip from Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. The old part of our town had been an important Revolutionary-era port, and it was not unusual to see bellringers in colonial garb walking down the sidewalks, or parades of minutemen with canon and fife. Early each morning, I light a candle and immerse myself in the words of the morning office, which is a form of prayer. Today’s lesson from Acts ended with an evocative phrase: “beyond Babylon.”

Early each morning, I light a candle and immerse myself in the words of the morning office, which is a form of prayer. Today’s lesson from Acts ended with an evocative phrase: “beyond Babylon.” money, the pillaging of goods from the end of the earth, the enslavement of human bodies and souls to the pleasure of the rich and the voracious, all-consuming demands of commerce.

money, the pillaging of goods from the end of the earth, the enslavement of human bodies and souls to the pleasure of the rich and the voracious, all-consuming demands of commerce. that engaged beauty and hope and tenderness? How can you be a part of making that happen, not only for yourself, but for others?

that engaged beauty and hope and tenderness? How can you be a part of making that happen, not only for yourself, but for others?

This afternoon, I had the opportunity to go behind-the-scenes at the National Gallery of Art, to tour the labs where skilled conservators work to preserve priceless works of art. At one table, a conservator examined a painting slowly under a microscope. Near a window, a woman in a black silk gown smiled enigmatically from a canvas by Van Dyke. By another window, a man wearing magnifying lenses worked painstakingly on a canvas by Fra Angelico, a painting of the entombment of Christ.

This afternoon, I had the opportunity to go behind-the-scenes at the National Gallery of Art, to tour the labs where skilled conservators work to preserve priceless works of art. At one table, a conservator examined a painting slowly under a microscope. Near a window, a woman in a black silk gown smiled enigmatically from a canvas by Van Dyke. By another window, a man wearing magnifying lenses worked painstakingly on a canvas by Fra Angelico, a painting of the entombment of Christ.