Last week, I spent a few days in the home of a long-time friend, who is dying. She was fragile and gaunt, could barely move her body in its bed, had not eaten in weeks. Together, her husband and I tended her: took her to the bathroom, smoothed her bed, brought her cups of water. When she dozed, we talked.

He is a philosopher, one of the better-known ones of the late-twentieth and early twenty- first centuries. And so, when he read about the new healthcare proposal, he leapt right over the details of what was and was not in it, and summed up the situation: We need a more robust debate about public versus private goods.

first centuries. And so, when he read about the new healthcare proposal, he leapt right over the details of what was and was not in it, and summed up the situation: We need a more robust debate about public versus private goods.

I was amazed. I tried to think of the last time I had heard an issue summed so succinctly, and could not. But, of course, he was right. When the founders of our nation crafted the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, they sought to create a republic, a respublica, which means, “a commonweal,” or “a public interest.” Both words imply a sense of shared good: that there are good things, desirable and necessary things, that we cannot have alone; things that we can only have if we give them to one another.

In the United States, of course, that ideal has always been in tension with another ideal:  that of the independent individual, the loner who needs no one and nothing to survive. The first Europeans to come here needed that mentality: they were leaving behind everything that made life “civilized” — their homes, communities, extended families, books, land, commerce, furniture — in order to seek something else that they had not found: wealth, freedom of conscience, adventure, a different kind of liberty. (I omit mention of the slaves who first came here in 1619; I’m not sure what they were seeking, but coming here wasn’t a choice they got to make. Once they arrived, I’m guessing they were seeking to make the best of a bitter lot, or to break away and try again.)

that of the independent individual, the loner who needs no one and nothing to survive. The first Europeans to come here needed that mentality: they were leaving behind everything that made life “civilized” — their homes, communities, extended families, books, land, commerce, furniture — in order to seek something else that they had not found: wealth, freedom of conscience, adventure, a different kind of liberty. (I omit mention of the slaves who first came here in 1619; I’m not sure what they were seeking, but coming here wasn’t a choice they got to make. Once they arrived, I’m guessing they were seeking to make the best of a bitter lot, or to break away and try again.)

The thing is that both of these ideals are good ones (minus the slaves): We flourish best under circumstances that allow some self-determination, and we also need the good things that come with community: education, friendship, infrastructure, the fruits of trade, support when things in our lives go badly wrong.

During my lifetime, however, the discussion of public goods has developed an odd character. Often, those goods are spoken of in derogatory ways, as if they were good enough for those who need them (but only those who are damaged would really admit the need). We privilege the car over the train or bus; the homeschooler over the families who use public schools; the desires of the sports enthusiast over the need of communities to keep their children safe from gunfire; the right of the industrialist to pollute over the common-weal of clean water and breathable air (without asking how necessary the product of that industry really is). In all these things, our public conversation allows the so-called “rights” of the individual to predominate over the “goods” of the community. And if anyone dares to speak up for the common goods, we have a rejoinder for him or her: “that’s redistribution.”

And if it is, is that a problem? Generosity used to be seen as a virtue. It was considered good to help others, righteous to meet the needs of the poor, virtuous to contribute to the upbuilding of the community. No less a figure than St. Paul, upon leaving the city where he had expended more missionary effort than in any other place, reminded them, “You yourselves know that these hands of mine have supplied my own needs and the needs of my companions. In everything I did, I showed you that by this kind of hard work we must help the weak, remembering the words the Lord Jesus himself said: ‘It is more blessed to give than to receive.’” (Acts 20:34-35)

The rub is in that one word: weak. No one wants to be among the weak, but the truth is, none of us can avoid it forever. Illness, unemployment, dislocation, war, pain, the demands of caring for others, even the urgencies of love, will, inevitably, mean that, at some point, we need something from one another. I cannot drive my car out of the driveway without someone to build a road; cannot give birth without someone to attend me; cannot see my friend to a peaceful and holy death without the ability to purchase medicine to ease her pain. Does this make me a “taker”? Of course it does, but in other ways, I give.

That, of course, is what a respublica was intended to be: a common space in which our gifts and ideas can be shared with one another for our mutual flourishing. It was intended to be mutual, and it was intended for more than mere survival. In caring for one another, we live into our fullest vocation as human beings.

Of course, there is a secondary debate here: whether it is ennobling to give when that giving is compulsory (as in a national system of taxation). In a world of small towns and villages, that might be a relevant question. In such a world, we would most likely know who was in need; we’d know them by name and be able to reach out, one on one. But the truth is that many of us (most of us?) no longer live on that scale. Our cities are too large for the intimacy of that kind of giving, our countryside too spread out. The Europeans settled their land in villages, clusters of homes surrounded by fields, but we settled ours in ranches and plantations, in which one family often lives hours from their nearest neighbors, even by car. We no longer know who is in need or how to help them; that’s why we build networks of care in order to do the work that keeps us human.

It may sound corny, but when I pay my taxes, I am glad to think of children going to school, of policemen patrolling streets, of clean water running from taps all over this nation because of the check that I am writing. More: I am proud to think of people in South Sudan being fed, of scientists working to cure ebola or limit the spread of the Zika virus, of refugees building new lives, just as my grandparents and great-grandparents had to do.

Martin Luther King, Jr., used to speak of the Beloved Community, which is another name for a Republic. It takes the idea of a republic and emphasizes its moral and spiritual foundations. “In the Beloved Community, poverty, hunger and homelessness will not be tolerated because international standards of human decency will not allow it. Racism and all forms of discrimination, bigotry and prejudice will be replaced by an all-inclusive spirit of sisterhood and brotherhood.” (from the King Center website)

The African word, ubuntu, has a similar sense. It means, “the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity.” Or, put another way, “In your welfare lies my welfare.” Try looking that up in Google, and you’ll find a lot of individualist memes, things like: “Don’t Worry, I’m working my ass off every day so you can drink, smoke and tattoo your welfare & unemployment checks away; it’s OK, really!” (That’s one of the more polite ones.)

Is that the world you want to live in? Or is it time to remember that the root of “commonwealth” is “commonweal”? What things should be shared goods? What dignity can we bring one another through what we offer and through what we receive? In what ways are we impoverished when we care only for “our own”?

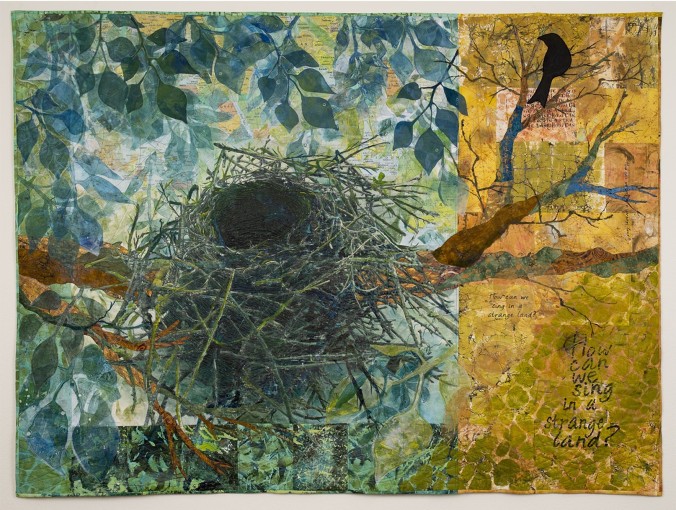

“How Can We Sing in a Strange Land,” by Bobbi Baugh, at bobbibaughart.com.